By Akriti Kharbanda, PhD

Scientist II, Discovery and Molecular Engineering (DME)

Where It All Began

Ever since I was eight years old, all I wanted was a scientist Barbie. Every Christmas and birthday I would ask, “Dad, please can I get a scientist Barbie so I can play scientist like you?” Unfortunately, scientist Barbie didn’t exist yet, so my dad got me the next best thing: experience. He would take me into the lab with him every weekend. I thought my dad was the coolest dad ever (still do). When I was a bit older, he would let me pipette some water between tubes or show me cells under the microscope. I was in awe of him, but also in awe of what he did. I couldn’t believe that there was a job in the world in which you were exploring the human body and, as I used to call cells, “the body inside my body.” That was it. I knew then that I wanted to be a scientist just like my dad; I would be scientist Barbie.

Throughout school, I had a few changes of heart on careers before landing on a doctor – an oncologist specifically because my life has persistently been overcast by the malignant shadow of cancer. My grandfather passed before I was born from Acute Myeloid Leukemia. My closest cousin, Ayesha, was diagnosed with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) at 12-years-old. Two years later, Ayesha’s brother, Krish, was also diagnosed with ALL at age two. Many other family and friends have suffered – my best friend’s mother, another cousin, an uncle – and all the surrounding caretakers. Krish achieved remission on his fourth birthday, but Ayesha passed away in hospice at 16. I ended college with my final change of heart – I realized that a doctor could try to restrain the shadow and maybe win some battles, but a scientist will devote their life to raising the sun and winning the war.

A New Vision of Discovery Science

So, I devoted my life to science, but I did not know what ‘science’ entailed as a job. An enlightened vision of science took decades to build and continues to evolve through my experiences. As I began my academic career, one thing became clear – having passion is fundamental. One day, as I reviewed the final results for my first publication in an elevator, I exclaimed: “YES! Finally!” I then heard a delicate voice behind me point to the film and say: “is that going to kill my cancer?” I faced the wheelchair bound gentleman with tears in my eyes and simply said: “I hope so, sir, one day.” On tough workdays, I think about that humbling moment to reignite the passion for this career.

Over time I formalized my envisioned recipe for science: a profound necessity to be curious and creative, a sense of fulfillment from uncovering and sharing knowledge, and oh, a teaspoon or so of serendipity. And I finally found a full-bodied taste of the career I chose. To reach this final recipe, I reflected on my own instances of discovery by destiny. My thesis project during graduate school began from an accident. My lab utilized a naturally occurring molecule to study an interaction between two proteins and how this interaction affects the function of these proteins. I accidentally used the wrong cells in my experiment – cells that happened to be derived from a patient with an untreatable form of lung cancer. Guess what? The small molecule killed the lung cancer cells!

This observation gave me a tourist visa for a journey into this molecule and its capacity to treat an untreatable form of lung cancer. I wrote a hitchhiker’s guide at the end of my trip to share with the scientific community. With a tourist visa, I was only able to scratch the surface of this subject, but I am confident in its power to make a significant impact in the fight against lung cancer. I recognized that sharing with humility will only strengthen the reliability of my findings. So, I handed over the hitchhiker’s guide to my fellow scientists for deeper analysis to prove that the answer is not simply ‘42.’

I may never witness the clinical impact of my work, but the fellowship of the scientific community will accelerate the evolution of the discovery into a better future for patients.

Meeting Vor Bio

After starting my next job as a scientific writer, I quickly missed the creativity, problem-solving, and comradery of bench science. I began searching for a scientist role in biotech and came  across this position that seemed to utilize all the hard and soft skills I had developed. The position was in a research group called Target Discovery at a company called Vor Bio. I remember reading the core values (passion, humility, and fellowship) in preparation for the interview and all I could do was smile because these values have been the predominant drivers of my career so far. Coincidence? I think not! One interviewer explained that this position was a “purple unicorn” because it required two unique skill sets hard to find in one person. That evening, I went to a local bookstore to buy a book but left with just a pen instead (see photo). There was my teaspoon of serendipity.

across this position that seemed to utilize all the hard and soft skills I had developed. The position was in a research group called Target Discovery at a company called Vor Bio. I remember reading the core values (passion, humility, and fellowship) in preparation for the interview and all I could do was smile because these values have been the predominant drivers of my career so far. Coincidence? I think not! One interviewer explained that this position was a “purple unicorn” because it required two unique skill sets hard to find in one person. That evening, I went to a local bookstore to buy a book but left with just a pen instead (see photo). There was my teaspoon of serendipity.

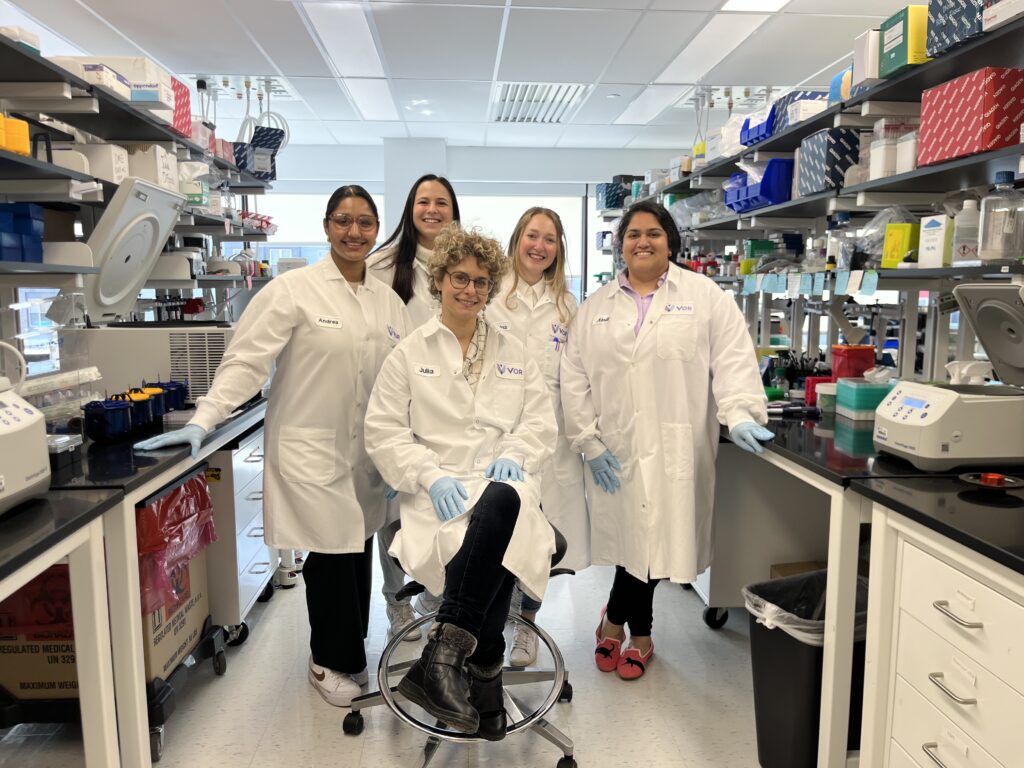

At Vor Bio, the “I” of academia became the “Us” of industry. Everyone here is driven by the singular goal of impacting patients’ lives. The most empowering moments in my career so far have been the stories of the patients who have visited and shared their experience.

This “Us” enables a faster route to their survival. This “Us” is only emboldened by industry’s science strategy, which I call ‘creativity under constraint.’ One might think that constraints will hinder creativity, but I think these constraints promote more out-of-the-box thinking, resourcefulness, and my favorite part, a special bond with your colleagues – the “Us.”

Just Getting Started

All my experiences have led me here. I thrived in academia with the flexibility to explore all angles of an observation. The challenge was the acceptance that I may never know it all. As Professor Dumbledore once said in the Harry Potter series: “It is the unknown we fear, nothing more.” In industry, I am learning to admire the “know all that you need to know” mentality because it is reinvigorating the curiosity and creativity I had as a little girl. Last Christmas, I bought myself a gift, wrapped it and put it under the tree with a “from dad” tag. Christmas morning, my dad grabbed

the wrapped box with confusion as he thought I didn’t wrap this gift. The tag isn’t even my handwriting. Nonetheless, he handed me the gift saying, “this might be a surprise for both of us.” I smiled and opened the gift; my dad cried for maybe the second time in his life because he had finally given me scientist Barbie almost 30 years later.

I enjoy the creativity, curiosity and connection of science, but just like my dad, and probably even scientist Barbie, my principal motivation to be a scientist has remained the same since the beginning of my career—let’s save some lives!